Latest News

OUR WORK

- 03 Jan 2026: Anaemia Screening Camp

- 28 Nov 2025: Anaemia Screening Camp

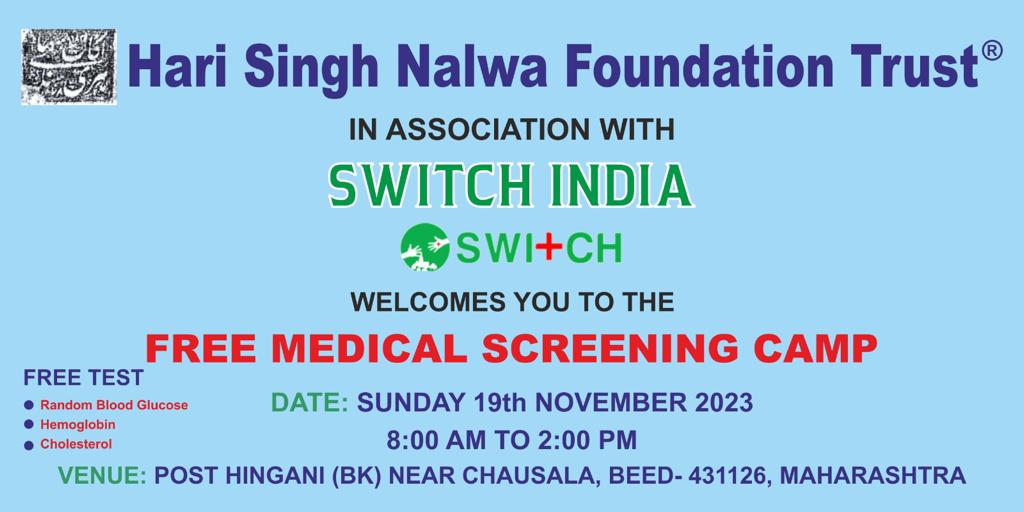

- 19 Nov 2023: Medical Camp, Beed, Maharashtra

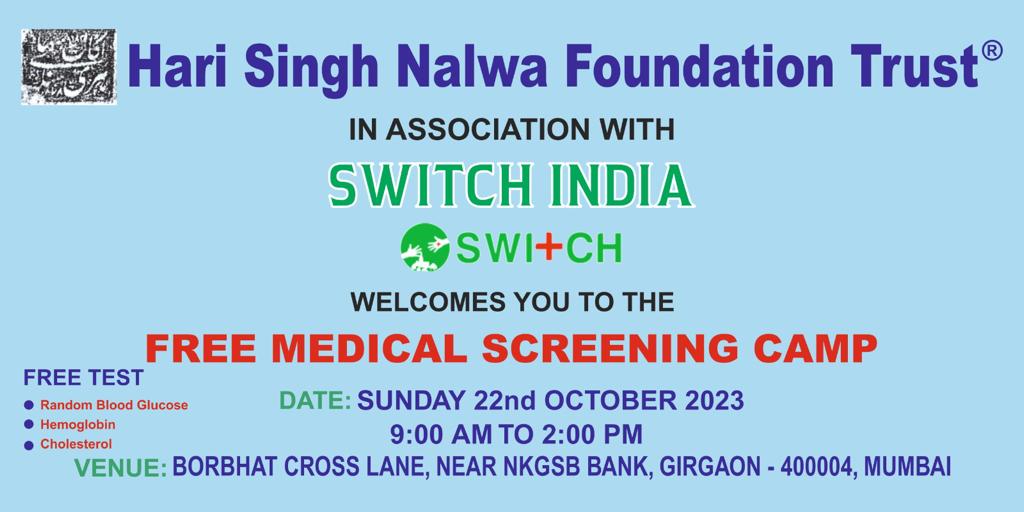

- 22 Oct 2023: Medical Camp in Girgaon, Mumbai, Maharashtra

- 16 Sep 2023: Medical Camp in Vidya Bal Vihar, New Delhi

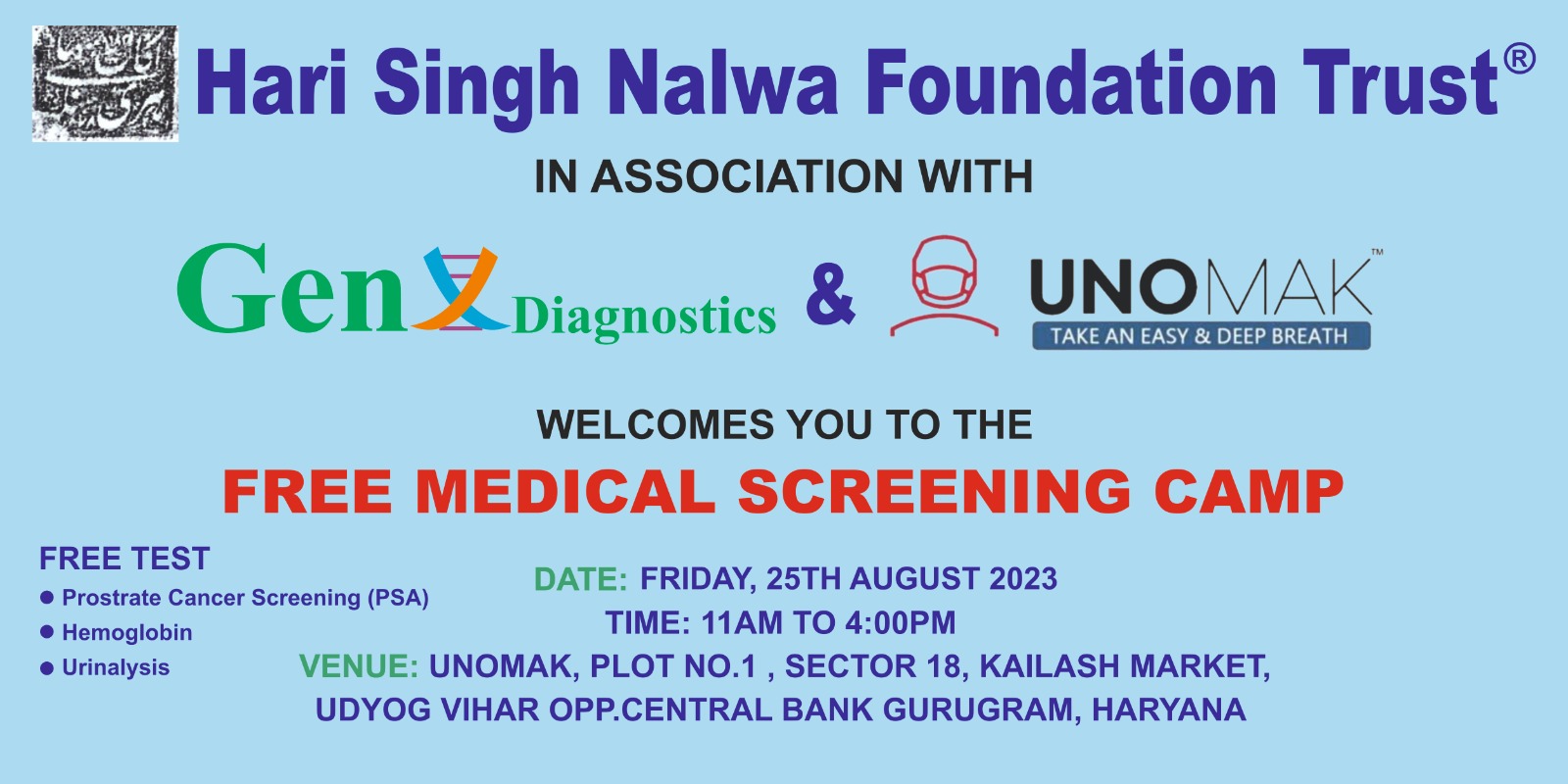

- 25 Aug 2023: Medical Camp in Gurugram, Haryana

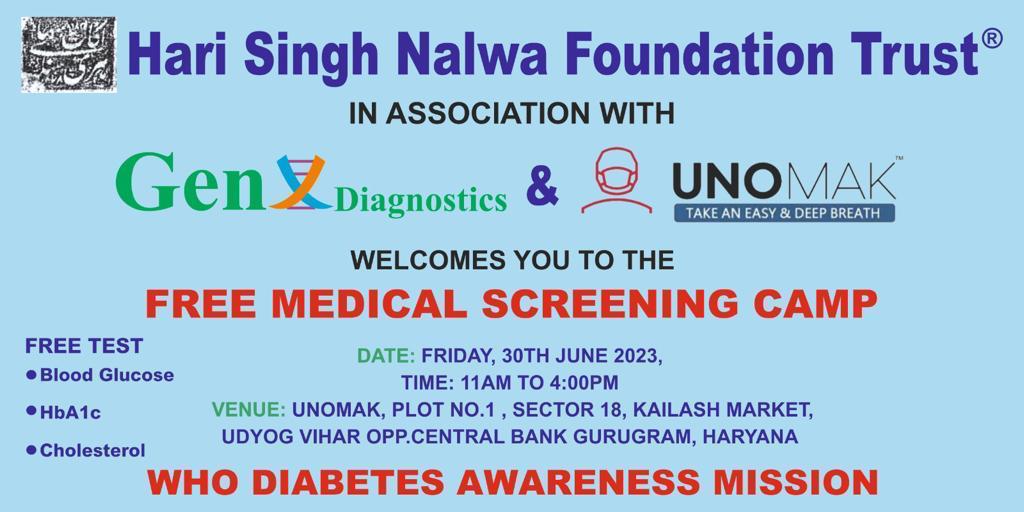

- 30 Jun 2023: Medical Camp in Gurugram, Haryana

- 11 Jun 2023: Medical Camp at Aya Nagar Village, New Delhi

- 18 Dec 2022: Medical Camp at Mangolpur Kalan Village, Delhi

- 15 Dec 2022: Medical Camp in Lawrence Road Industrial Area, Delhi

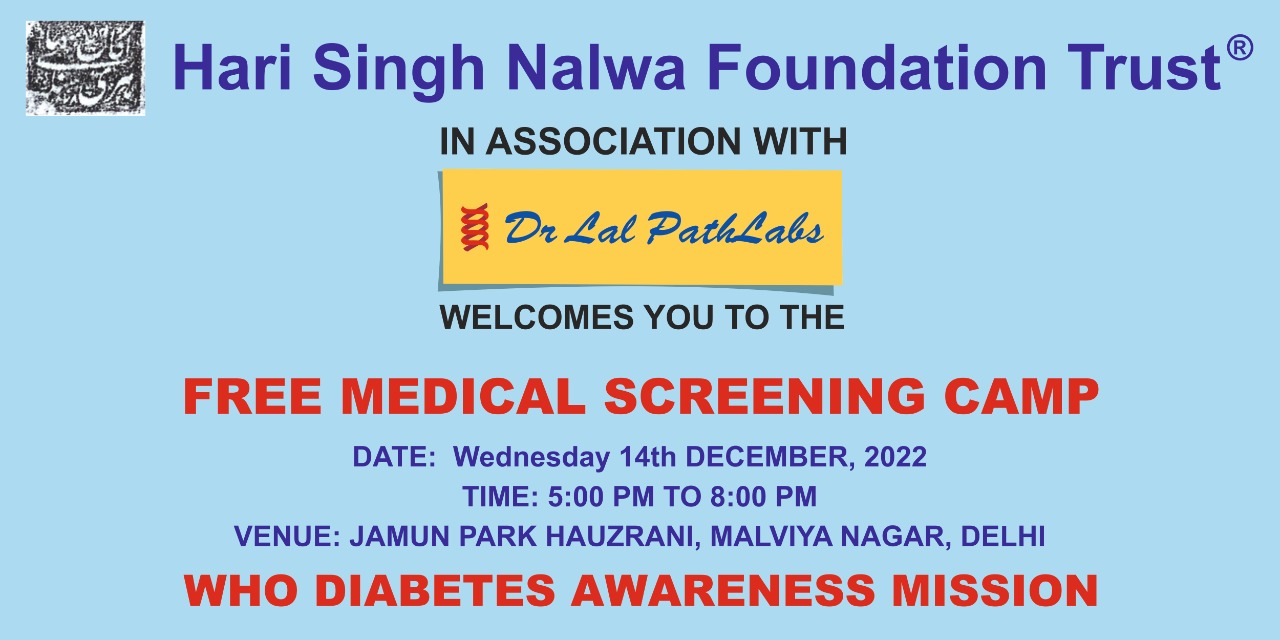

- 14 Dec 2022: Medical Camp at Jamun Park, Malviya Nagar, New Delhi

- 13 Dec 2022: Medical Camp at Mangolpur Kalan Village, Delhi

- 30 Nov 2022: Medical Camp at Chattarpur Village, New Delhi

- 01 Oct 2025: Unveiling of the Statue of Hari Singh Nalwa

- 30 Apr 2025: 188th Death Anniversary

- 22 Mar 2025: Lahore Darbar in Australia

- 21 Mar 2025: The Lions of the Sikh Empire

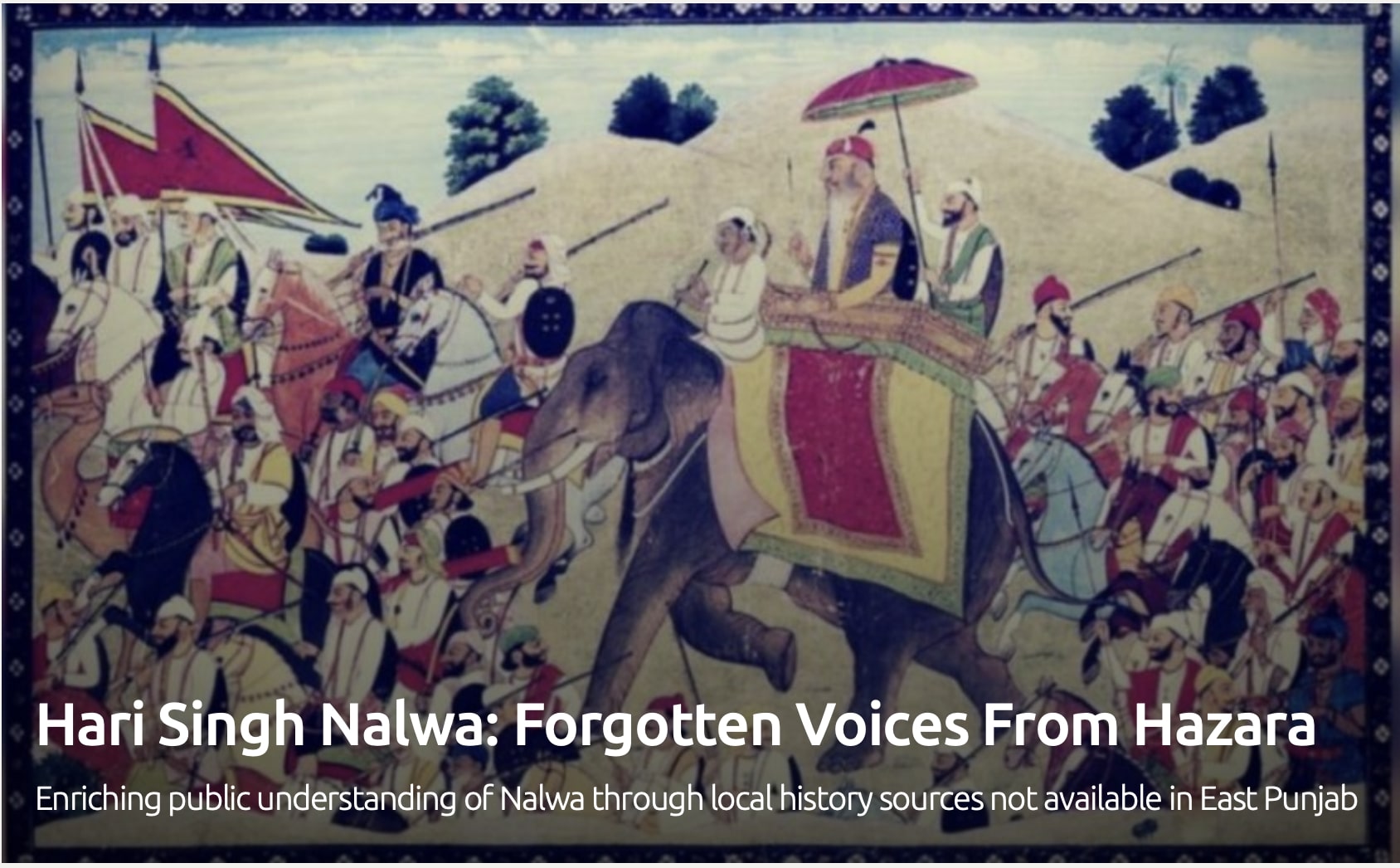

- 04 Jun 2024: Forgotten Voices From Hazara

- 06 Jan 2023: First Sikh History Congress

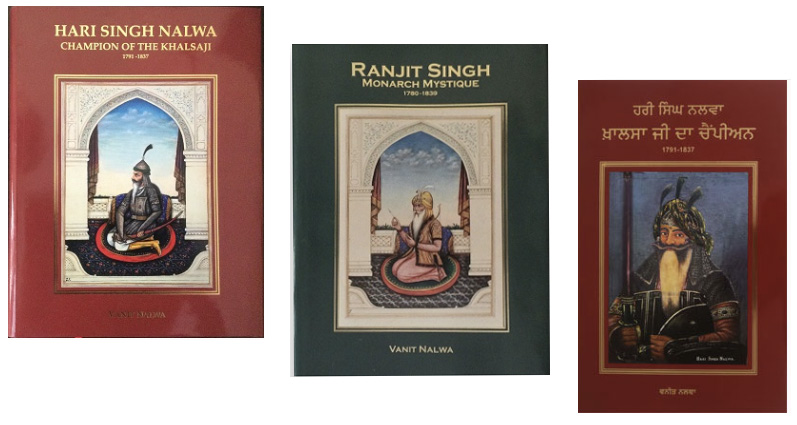

- 01 Jan 2022: Ranjit Singh—Monarch Mystique 1780-1839

- 06 Mar 2021: Support for the Global Social Foundation

- 28 May 2012: Why am I a Historian

- 21 Oct 2009: A Legacy of Valour

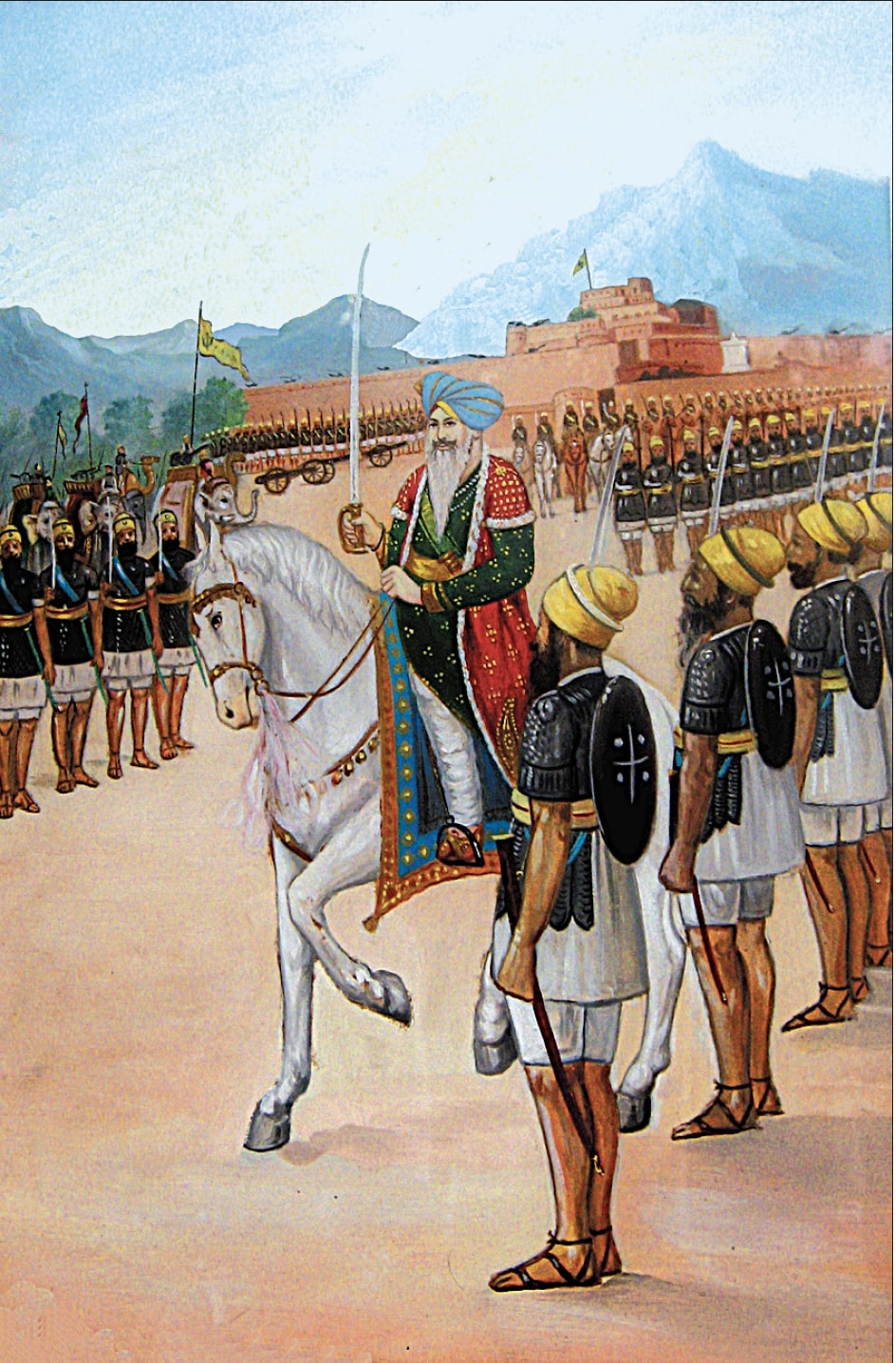

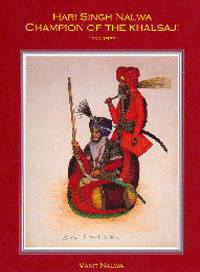

- 13 Jan 2009: Hari Singh Nalwa—Champion of the Khalsaji

- 23 Feb 2006: National Museum Seminar cum Workshop

ABOUT US

03 Feb 2006 THE TRUST

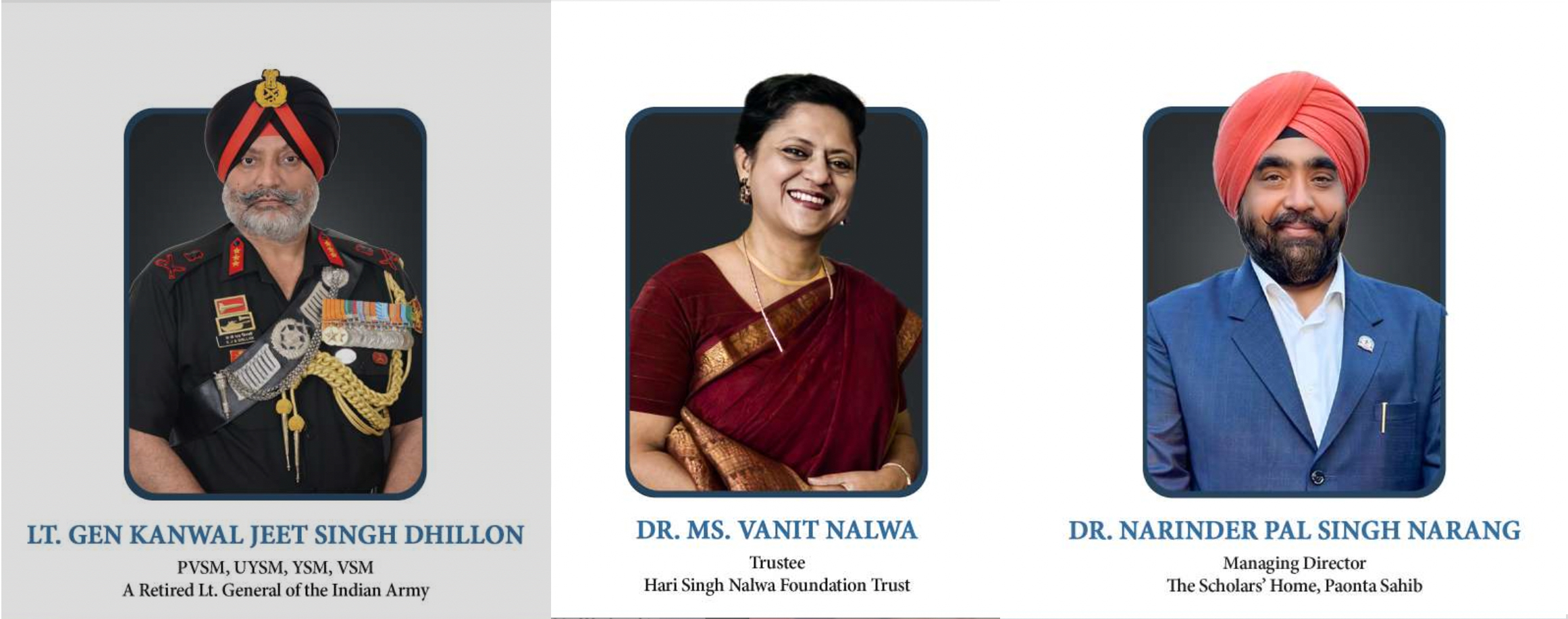

13 Jan 2024 THE BOARD

13 Nov 2024 Vanit Nalwa

11 Dec 2024 Preeti Nalwa

11 Dec 2024 Harjit Singh Nalwa

11 Dec 2024 Avijit Singh Nalwa

12 Dec 2024 Koplin Kandhari

IN THE NEWS

28 Nov 2025 Strengthening Public Health Infrastructure

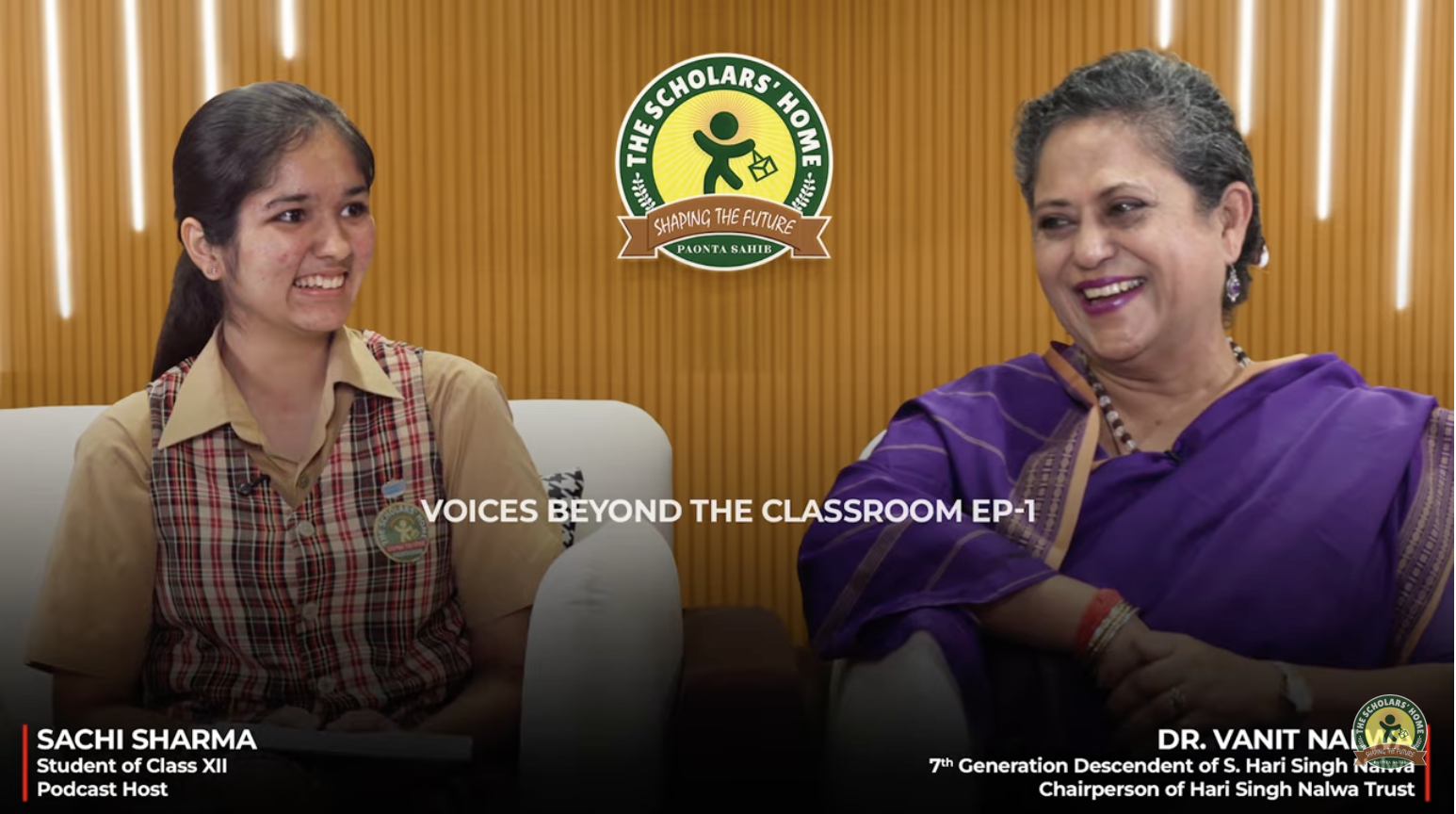

01 Oct 2025 Voices beyond the Classroom

09 Jun 2025 Lahore Darbar presentation in Australia

13 May 2025 The Koh-i-Noor—A Contraband Item?

03 May 2025 Honouring the Legacy

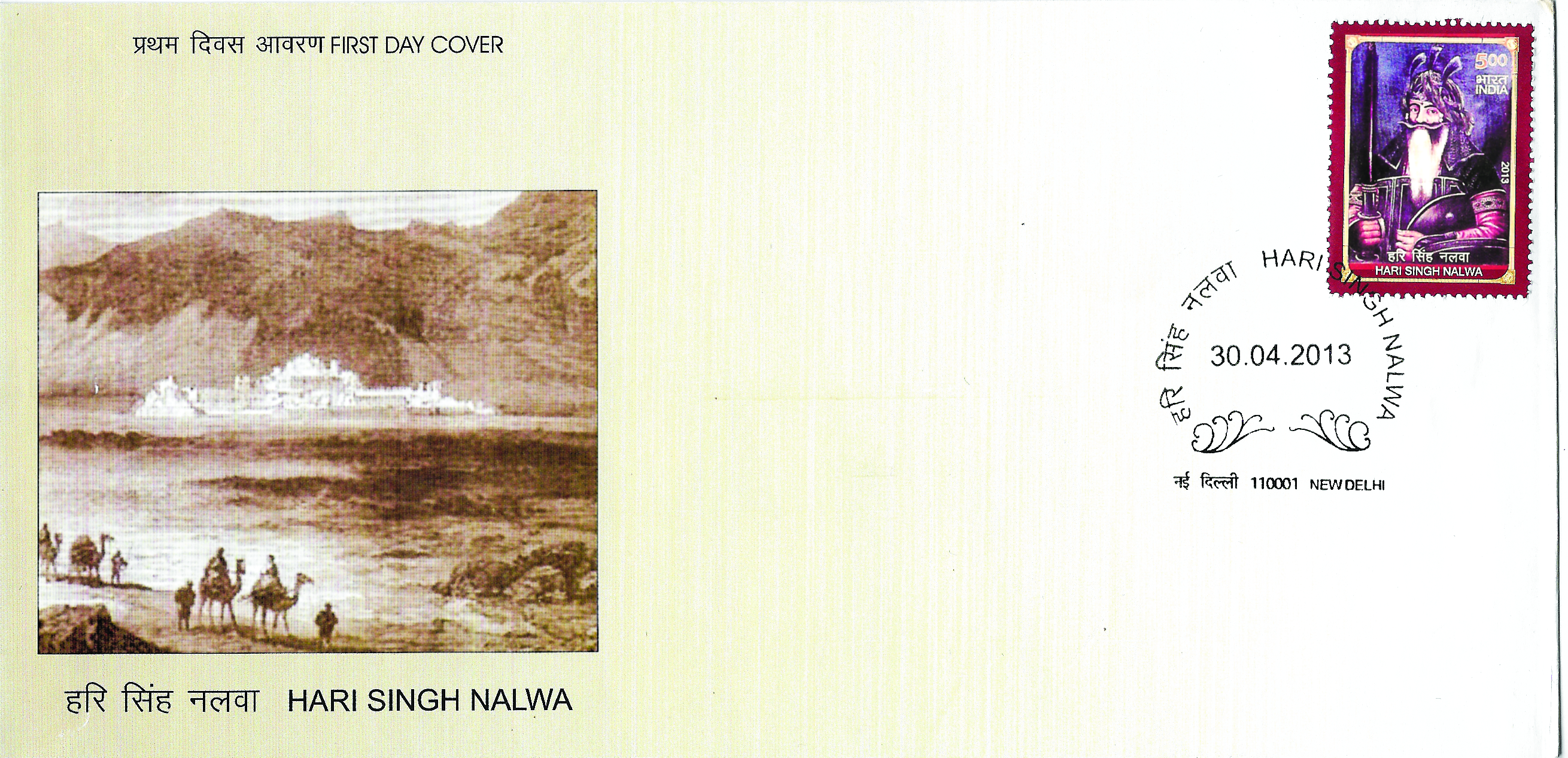

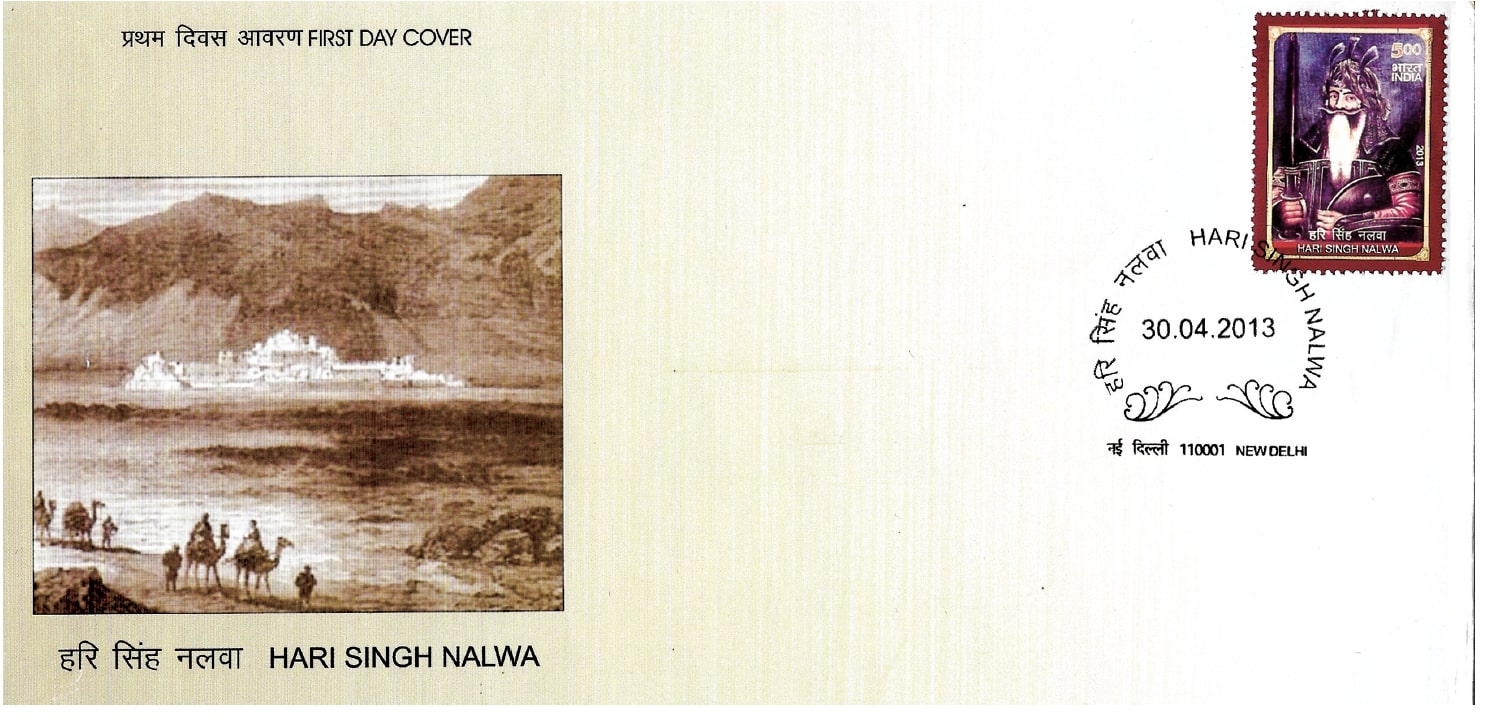

02 Jul 2024 First Day Cover

11 May 2024 Win a Hari Singh Nalwa First Day Cover

04 Feb 2024 Who was Arjan Vailly?

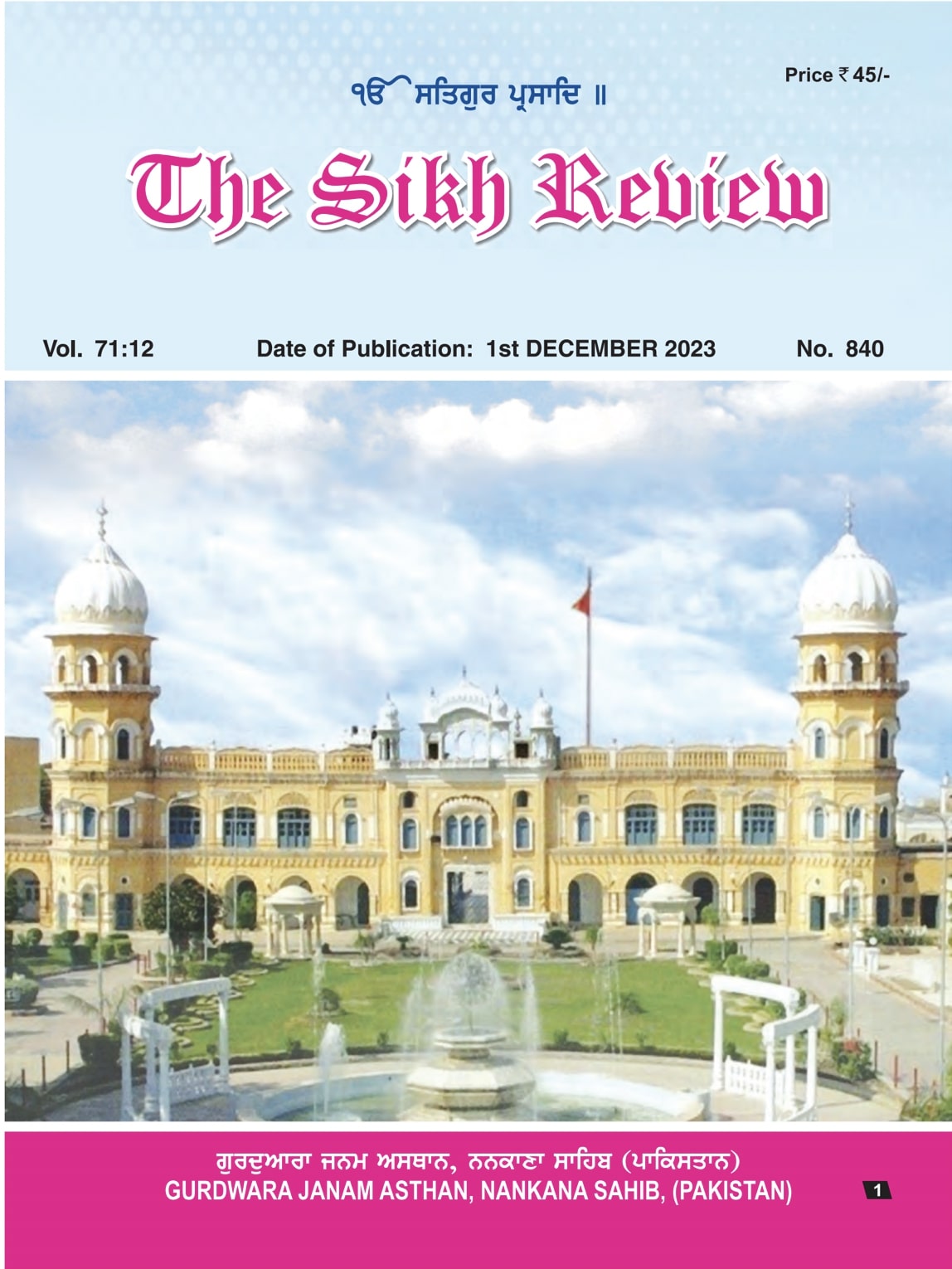

01 Dec 2023 After Hari Singh Nalwa

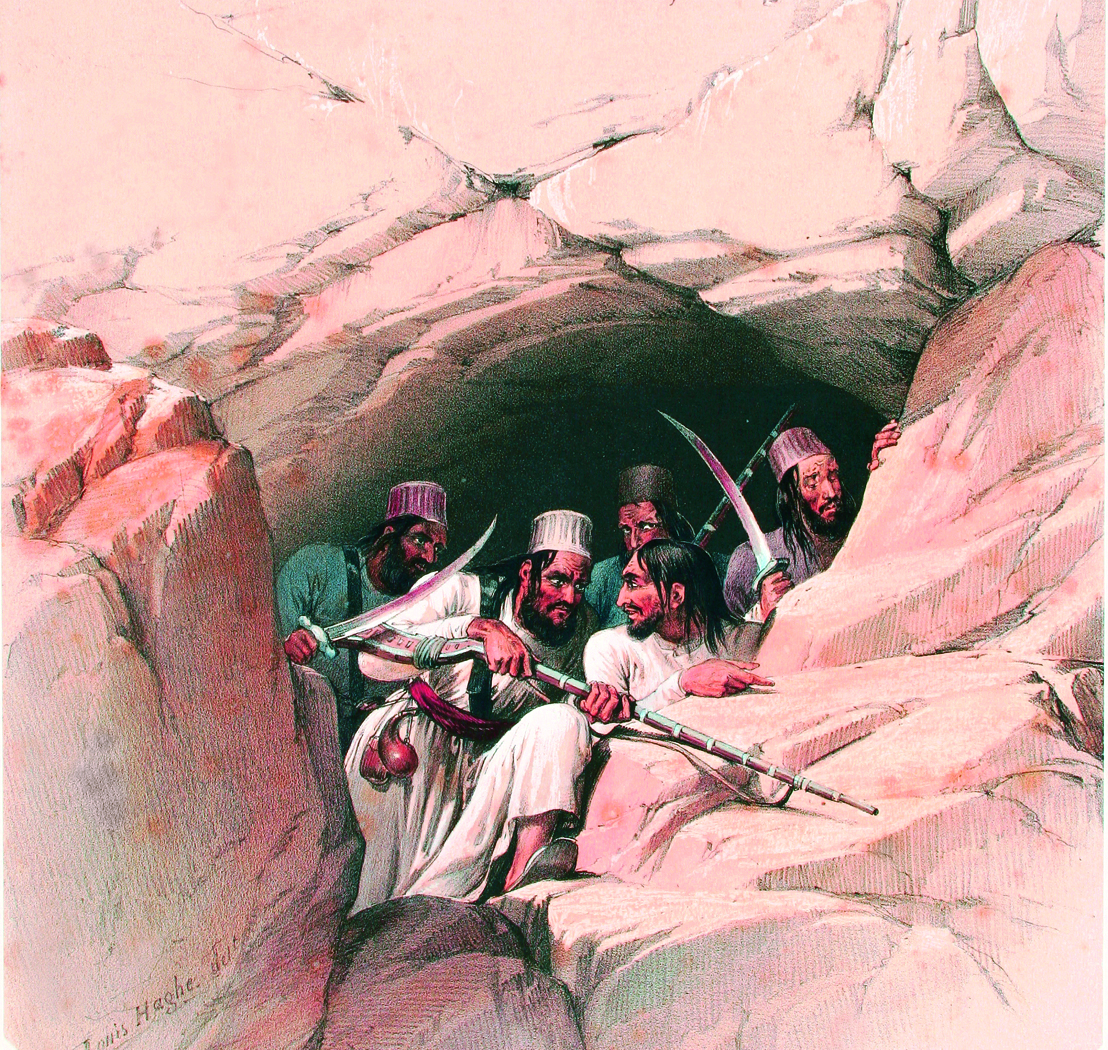

01 Dec 2023 I saw Huree Singh, Nulwa...

01 Dec 2023 Book Review "Ranjit Singh-Monarch Mystique"

30 Oct 2023 3-Day Cultural Fest on Sikh General...

11 Jun 2023 The Koh-i-Noor

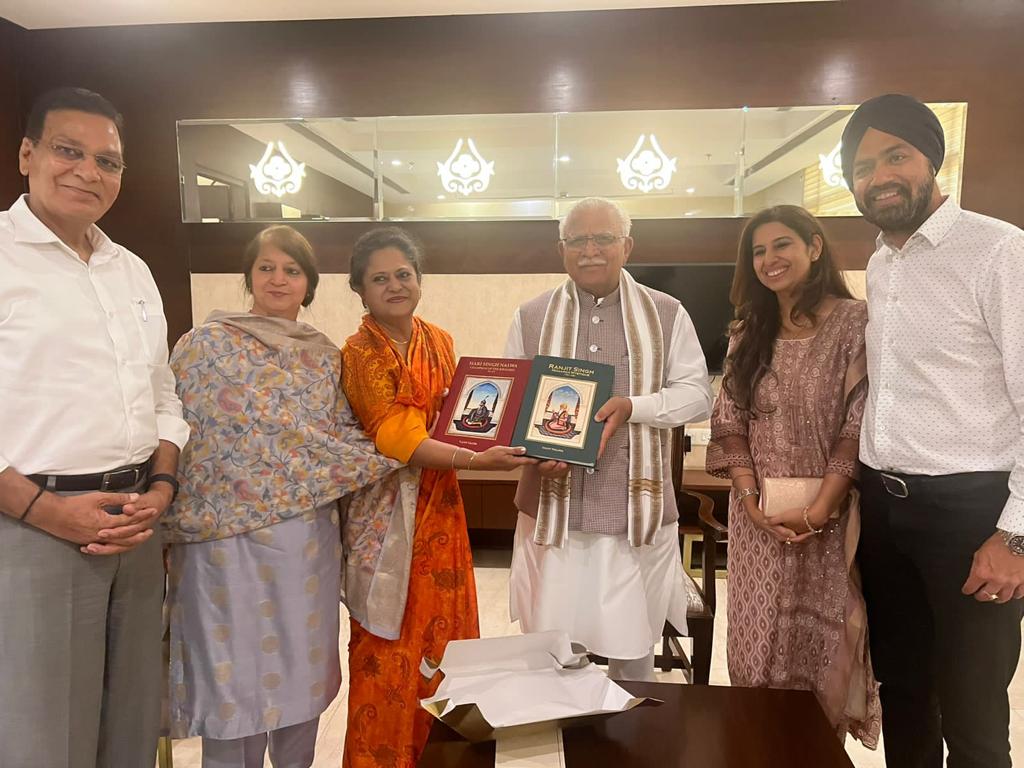

21 May 2023 Sh. Manohar Lal releases the twin-volume...

25 Feb 2018 New book reveals how...

23 Feb 2018 National Archives of India

01 Oct 2014 Hari Singh Nalwa History | EPIC

30 Apr 2013 Government of India releases a postage stamp...

14 May 2011 The Incident at Abbottabad

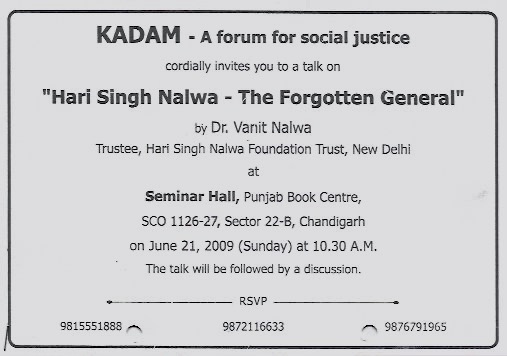

21 Jun 2009 Hari Singh Nalwa—The Forgotten General